The following article was written by Gillie Warren who had kindly given me permission to republish it on our website. Thanks Gillie!

The following article was written by Gillie Warren who had kindly given me permission to republish it on our website. Thanks Gillie!

(This is not my story. It was written by a journalist called Bill Simpson and published in the Courier-Mail in June 2003, although many may not have seen it.

I did help with the research, and Bill kindly gave me permission to reproduce the story in “Happenings”, our local newspaper at the time”. (Gillie Warren))

“Montville has had a unique Australian attraction for the past century without most people, including locals, having any idea.

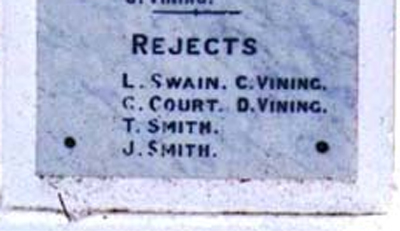

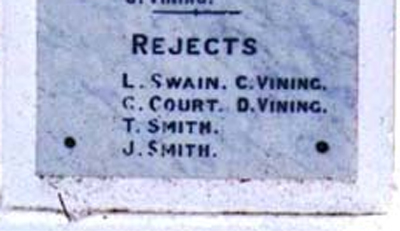

Secluded in the village is a war memorial which publicly reveals six Montville men who were rejected for service during World War I. The two-pillar monument at the centre of Montville’s memorial gates, unveiled on Remembrance Day 1921, carries names under three distinct headings: Enlistments (33 names), Fallen (6 names), and, at the bottom, Rejects (6 names); L.Swain, C.Court, T.Smith, J.Smith, C.Vining, D.Vining. Even more astonishing is the expectation by the experts that the six men almost certainly requested to be recorded as rejects.

Researchers agree the Montville memorial is the only one in Queensland, and possibly Australia, to identify rejects. So why were these men recognised publicly?

While no official records are known to exist, Victoria Barracks History Society Queensland curator Leo Walsh provides an account he considers close to the truth. The six men, Walsh says, would have volunteered. It was the Australian thing to do at wartime.

Some would have been rejected on medical grounds. Some would have been rejected because their jobs were essential to the war effort at home. Dairy farming and droving would have been among them. Some would have been rejected because of the number of other family members already enlisted. Whatever the reason, Walsh is certain the six men requested they be recognised as having volunteered. There were extreme social pressures at the time on young men to volunteer, and it was common, both in Australia and the UK, for men who refused to volunteer to receive a white feather from some disenchanted person in the community. The white feather was a symbol of cowardice. It was always presented in a public way so that others knew, and the objector was recognised for the rest of his life as a man not prepared to defend his country. The stigma stuck. To protect men who volunteered but were rejected for legitimate reasons, small communities around Australia formed “associations of the rejected”. They recognised these men in many different ways. One common way was a badge the men could wear to identify themselves as willing, despite their rejection. Walsh says Montville appears to have been unique in recognising its six men by naming them on its memorial. “It’s the only example we have heard,” he says. Interestingly, he says that rather than being disgraced by being publicly identified, the Montville men were given a salute for their willingness to enlist and serve their country.

History professor Ken Inglis also refers to associations of rejected volunteers in his book, Sacred Places: Monuments in the Australian Landscape. He says the associations petitioned committees to put (the volunteers’) names on their tablets (memorials), but with little success.

When the Montville RSL sub-branch disbanded, members joined surrounding branches, mostly Maleny or Mapleton. Mapleton sub-branch secretary Roley Rowsell says his information supports what Walsh says. Elderly Montville residents recalled stories of the six men who volunteered. “The word is that these six men asked to be recorded as rejects on the memorial as a means of showing that they were there (at war) in spirit, if not in person,” Rowsell says. Did he think that, maybe, there should be a more sensitive section for the six men on the memorial? “Hell, no,” he thunders, “That’s history. You don’t change history. It was the language of the day. It’s like, in those days to be gay meant you were happy and carefree. It means something altogether different now. No, damn it, leave it as it is.

Elmslie Vining’s father, Daniel, was one of Montville’s famous rejects. So was his Uncle Charles, Daniel’s brother. Vining, who left Montville at the age of 11 and now lives at Scarborough, says his father told him both he and Charles had volunteered, but were rejected on medical grounds. “Dad told me that he had rheumatic fever at 20 or 21,” recalls Vining, now 74, “But the main thing that kept him out (of the war) was that he had osteoarthritis or osteoporosis, or something like that, of the left heel. The back of the heel had to be removed. So he couldn’t wear boots or shoes without getting horrific blisters. He was disappointed. He didn’t want to be seen to be shirking his share (of war duty).” Vining says his Uncle Charles had a spinal condition from a horse riding accident as a young man and spent the rest of his life “bent almost double”. “I never heard any derogatory remarks about the men who could not serve,” he says, “It seemed to be acceptable to the community.”

One of Montville’s oldest residents, Madge Glover, recalls Thomas and John Smith were brothers from a large family. Four sons were accepted for service, two were of school age, and Thomas and John were rejected, probably because the farming family had already made a big enough contribution.”

Charlie Court was an older brother of Bert Court, a school student for some time at Montville, and later a pupil-teacher. The Courts had moved to Palmwoods in 1909, but possibly Charlie stayed in Montville; there is a Mrs C.Court listed in the 1925 Montville telephone directory. Leslie Swain was a young farmer at Flaxton. His children Janet Swain and John Swain were enrolled at Montville school in 1920 and 1921. Mr Swain was President of Montville Bowling Club in 1939. Recently his granddaughter, child of a younger daughter who attended school in Flaxton, contacted me, wanting information about her grandfather, his farm and life. She was tickled pink to hear that her grandfather was actually a very, very special person, a Reject in fact! (Gillie Warren)

The following article was written by Gillie Warren who had kindly given me permission to republish it on our website. Thanks Gillie!

The following article was written by Gillie Warren who had kindly given me permission to republish it on our website. Thanks Gillie!